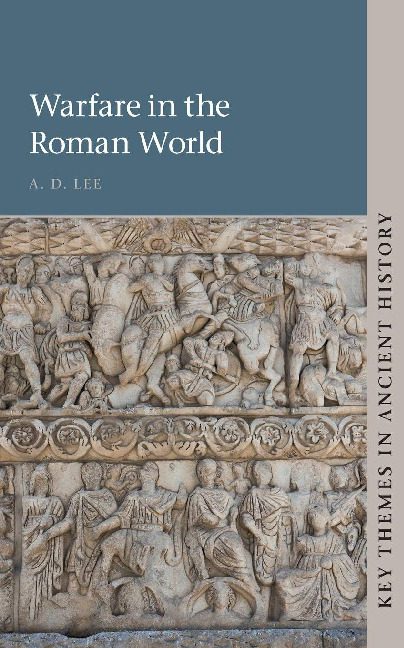

The Roman practice of decimation stands as one of history’s most brutal and psychologically calculated methods of military discipline. Rooted in the Latin term decimatio—meaning “removal of a tenth”—this punishment involved the systematic execution of one in ten soldiers within a unit guilty of collective offenses such as cowardice, mutiny, desertion, or insubordination. Designed to instill fear and reinforce hierarchical authority, decimation transcended mere physical punishment; it served as a ritual of terror that underscored the Roman military’s unyielding demand for absolute obedience. Historical accounts from Polybius, Livy, and later chroniclers reveal that decimation was sparingly but strategically deployed, often during crises of morale or leadership. Its implementation varied across centuries, from the early Republic’s wars against the Volsci to Crassus’ ruthless suppression of Spartacus’ revolt. Beyond its immediate brutality, decimation shaped the Roman legionary ethos, balancing the pragmatism of collective punishment with the destabilizing risks of mass executions. This report explores the origins, procedures, historical applications, and enduring legacy of decimation, contextualizing its role within the broader framework of Roman military discipline.

Origins and Evolution of Decimation in Roman Military Doctrine

TL;DR: The Roman Practice of Decimation

Decimation was an extreme form of military discipline in ancient Rome, where one in ten soldiers from a disgraced unit was executed to enforce obedience and deter insubordination. First recorded in the early Republic, the practice was used strategically, from wars against the Volsci to Crassus’ crackdown on mutinous troops. Soldiers were forced to participate in the execution of their comrades, reinforcing fear-driven discipline. While effective in maintaining order, it risked resentment and was gradually phased out during the Imperial era due to morale and manpower concerns.

Key Aspects of Decimation

| Aspect | Details |

|---|---|

| Origin | Derived from Latin decimatio (“removal of a tenth”). |

| Purpose | Enforce discipline, deter cowardice, mutiny, and desertion. |

| Process | One in ten soldiers chosen by lottery, executed by comrades. |

| Execution Methods | Stoning, clubbing, or stabbing. |

| Additional Punishments | Survivors demoted, given barley rations, exiled from camp. |

| Notable Uses | Volscian Wars (471 BCE), Crassus vs. Spartacus (73–71 BCE), III Augusta Legion (20 CE). |

| Decline | Phased out by late Empire due to morale concerns and manpower shortages. |

Comparative Roman Military Punishments

| Punishment | Offense | Method |

|---|---|---|

| Fustuarium | Theft, desertion, falling asleep on duty | Beaten to death with clubs |

| Decimation | Cowardice, mutiny, desertion | 1 in 10 executed, others punished |

| Centesimatio | Lesser offenses | 1 in 100 executed (later alternative to decimation) |

| Mass Execution | Treason, large-scale mutiny | Entire units wiped out |

The Etymological and Conceptual Foundations

The term decimatio derives from the Latin decem (ten), reflecting the punishment’s mathematical precision: the removal of 10% of a unit’s manpower. While often associated exclusively with Rome, the practice had precedents in earlier Mediterranean armies. For instance, Alexander the Great reportedly executed 6,000 soldiers for mutiny in 324 BCE, though this was a mass execution rather than a systematic decimation6. The Romans institutionalized the practice, embedding it within their military legal code as a deterrent against collective disobedience.

Polybius, writing in the 2nd century BCE, provides one of the earliest detailed descriptions of decimation. He notes that it was typically reserved for units that fled battle, deserted posts, or challenged authority—crimes deemed existential threats to the legion’s cohesion12. The punishment’s dual purpose was clear: to eliminate perceived weak links and to traumatize survivors into unwavering compliance. By forcing comrades to participate in the killings, commanders ensured that guilt and fear permeated the ranks, transforming soldiers into enforcers of their own subjugation35.

Legal and Cultural Context

Roman military law (ius militare) operated under a principle of extreme severity, prioritizing the collective over the individual. While minor infractions might result in flogging or reduced rations, capital crimes—including insubordination—carried the threat of execution. Decimation occupied a unique niche within this framework, as it punished groups rather than individuals, reflecting the legion’s dependence on unit cohesion. The testudo formation, for example, relied on each soldier’s precise positioning to protect the collective; any lapse jeopardized the entire unit4. Decimation thus served as a hyperbolic reinforcement of this interdependence, reminding soldiers that their lives were forfeit if they failed the group.

Cultural attitudes toward discipline also played a role. Roman society valorized virtus (courage) and disciplina (order), virtues that decimation ostensibly upheld. Yet the practice’s randomness—a lottery system determining victims—introduced an element of fatalism. Soldiers could not predict whether merit or misfortune would spare them, fostering a climate of anxious obedience6.

The Mechanics of Decimation: Ritual and Procedure

The Lottery of Death

When a unit was sentenced to decimation, the process followed a grimly methodical script. First, the offending cohort (typically 480 men) or legion (approximately 5,000 men) was assembled. Commanders publicly denounced the men’s crimes, emphasizing the shame brought upon the legion and the Republic (or later, the Empire). The soldiers were then divided into groups of ten (contubernia), each forced to draw lots—often straws of varying lengths—from a helmet or other receptacle. The soldier who drew the shortest straw was immediately clubbed, stoned, or stabbed to death by his nine comrades126.

This participatory aspect was crucial. By compelling soldiers to kill their peers, commanders deepened the psychological trauma, ensuring that survivors internalized the consequences of disobedience. As Livy recorded during the early Republic, even centurions and standard-bearers were not exempt; their executions were carried out individually, while the rank-and-file endured the lottery6.

Supplementary Punishments

Death was not the sole consequence. Survivors faced additional sanctions designed to compound their humiliation and suffering. They were often:

- Demoted to barley rations: Wheat was the standard legionary diet; barley, associated with animal feed, symbolized degradation6.

- Exiled from camp: Forced to bivouac outside fortified encampments, soldiers endured exposure and vulnerability to enemy attacks1.

- Stripped of honors: Decorations and promotions were revoked, erasing past achievements4.

These measures reinforced the message that survival did not equate to forgiveness. The unit’s identity was permanently marred, its reputation only restorable through exceptional future performance.

Historical Applications: Decimation as a Tool of Crisis Management

Early Republic: The Volscian Wars and the Foundation of Precedent

The earliest documented decimation occurred in 471 BCE under Consul Appius Claudius Sabinus Regillensis. After Roman forces faltered against the Volsci, Claudius ordered the execution of deserters and those who had discarded their weapons. Centurions and standard-bearers were individually scourged and beheaded, while the remaining soldiers underwent decimation. Livy notes that this “purged the army with blood,” reasserting control through terror6.

The Third Servile War: Crassus and the Pacification of Rebellion

Decimation’s most infamous application came during the Third Servile War (73–71 BCE), when Marcus Licinius Crassus faced Spartacus’ rebel army. After two legions broke ranks and fled battle, Crassus revived decimation—a punishment then considered archaic—to restore discipline. From the 500 survivors, 50 men were selected by lot and clubbed to death by their comrades. Plutarch suggests this act not only terrified Crassus’ own troops but also demoralized Spartacus’ forces, who realized they now faced a leader as ruthless as themselves65.

Imperial Era: Decline and Symbolic Deployment

By the Imperial period, decimation grew rare but retained symbolic potency. Emperor Augustus used it in 17 BCE to quell a mutiny, while Galba (r. 68–69 CE) deployed it during the Year of the Four Emperors. Tacitus recounts that Lucius Apronius decimated a cohort of the III Augusta legion in 20 CE after its defeat by Tacfarinas, a Berber rebel6. However, the practice faced criticism. The 6th-century Strategikon of Emperor Maurice explicitly banned decimation, arguing that it eroded morale and depleted manpower—a pragmatic shift reflecting the late Empire’s struggles to maintain recruitment6.

Psychological and Sociopolitical Implications

Fear as a Cohesive Force

Decimation’s effectiveness lay in its psychological precision. By randomizing victim selection, it circumvented accusations of favoritism but also instilled pervasive dread. No soldier, regardless of rank or bravery, could feel safe, fostering a climate where even whispered dissent risked annihilation. Polybius observed that survivors were “more afraid of their own comrades than the enemy,” a sentiment commanders exploited to ensure obedience12.

The Paradox of Unity and Resentment

While decimation theoretically strengthened unit cohesion, it risked fostering resentment. The Eastern Roman Emperor Maurice recognized this, noting that forcing soldiers to kill comrades could spark further mutinies or desertions6. Yet in the Republic and early Empire, the practice’s sporadic use—reserved for extreme cases—likely limited backlash. Soldiers perceived it as an extraordinary measure, a “necessary evil” to avert greater disasters.

Comparative Analysis: Decimation and Alternative Punishments

Spectrum of Roman Military Discipline

Decimation existed within a hierarchy of punishments:

- Fustuarium: Beatings with clubs, often fatal, for individual offenses like theft or falling asleep on watch4.

- Reduction in pay or rations: Economic penalties for minor infractions.

- Decimation: Collective punishment for capital crimes.

- Mass execution: Entire units annihilated for treason or repeated mutiny, as occurred under Augustus6.

Decimation’s uniqueness lay in its blend of collectivism and selectivity. Unlike mass executions, it preserved most of the unit’s manpower while still delivering a visceral warning.

Cross-Cultural Perspectives

Similar practices existed elsewhere. The 16th-century Huguenots decimated surrendering troops at La Rochelle, and Wallenstein’s Imperial forces used it during the Thirty Years’ War6. However, these post-classical examples lacked the institutional rigor of Roman decimation, often devolving into arbitrary massacres.

The Decline and Legacy of Decimation

Administrative and Moral Challenges

As the Empire expanded, maintaining legionary manpower grew difficult. Decimation’s attritional cost became pragmatically untenable, prompting shifts toward less wasteful punishments. The centesimatio (executing every hundredth man), introduced by Emperor Macrinus (r. 217–218 CE), reflected this trend6. Additionally, Christianization of the Empire introduced ethical objections to collective punishment, exemplified by the legend of the Theban Legion’s martyrdom for refusing to decimate Christians6.

Enduring Symbolism

Despite its obsolescence, decimation endured as a cultural metaphor for draconian discipline. Modern militaries occasionally invoked the term rhetorically, though none adopted the practice formally. In organizational theory, decimation symbolizes the trade-offs between fear-based control and group cohesion—a cautionary tale of leadership through terror.

Conclusion

Decimation was more than a punishment; it was a performative assertion of Roman military absolutism. By combining mathematical precision with psychological manipulation, it transformed soldiers into both victims and agents of discipline, reinforcing the legion’s hierarchical rigidity. While effective in crisis moments, its brutality ultimately rendered it unsustainable, clashing with the Empire’s evolving logistical and ethical realities. Yet as a historical phenomenon, decimation epitomizes the extremes to which societies may go to enforce order—a reminder of the dark interplay between power, fear, and survival in the ancient world.

Citations:

- https://allthatsinteresting.com/decimation-punishment

- https://www.historyextra.com/period/roman/decimation-roman-punishment-real/

- https://historychronicler.com/roman-decimation-the-grim-reality-of-blood-on-the-standards/

- https://www.unrv.com/military/discipline.php

- https://www.historydefined.net/the-history-of-decimation/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Decimation_(punishment)

- https://www.livius.org/articles/concept/decimation/

- https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/antichthon/article/decimatio-myth-discipline-and-death-in-the-roman-republic/504D6242E0621DE1B2CC0D32B92765E3

- https://www.reddit.com/r/etymology/comments/dekltg/the_word_decimation_comes_from_the_latin/

- https://www.reddit.com/r/AskHistory/comments/1hhmcd5/why_did_the_ancient_romans_consider_decimation_a/

- https://www.unrv.com/military/decimation.php

- https://www.ancient-origins.net/history-ancient-traditions/roman-decimation-0017137

- https://georgianera.wordpress.com/tag/punishment-of-decimation/

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Y1tMZ8FLoWY

- https://quod.lib.umich.edu/d/did/did2222.0003.605/–decimation?rgn=main%3Bview%3Dfulltext%3Bq1%3DRoman+history

- https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5184/classicalj.111.2.0141

- https://www.facebook.com/photo.php?fbid=922528993241204&id=100064523356918&set=a.621404423353664